Bounding Boxes and Bovine Nightmares

Okay, so now I’m in the deep end of learning. The proverbial safety bumpers have been removed. I completed Learn WGPU and now I have to do something myself?!

So I decided to start out simple: load in a new model. Seemed easy enough - find a free model online and drop it in. One “free obj” Google search later, and I have found a nice bull model. Loads of vertices and polygons. Boom. Done.

Problem #1 enter stage left. I naively swap out “cube.obj” for

“bull.obj” and hit cargo run. Crash. Instantly.

Ok, wtf. Why didn’t that work? Time to read the compiler error… of course - an “index out of bounds” error. Classic.

To spare you the boring details, I eventually figured it out. The new model file has no materials. So I hacked them in.

if materials.is_empty() {

let dummy_texture = texture::Texture::from_image(

device,

queue,

&image::DynamicImage::ImageRgba8(image::RgbaImage::from_pixel(

1,

1,

image::Rgba([255, 255, 255, 255]),

)),

Some("white"),

)

.expect("Failed to create placeholder texture");

materials.push(model::Material::new(

device,

"white",

dummy_texture.clone(),

dummy_texture,

layout,

));

}

Now we can expect a nice sheen on the models - with absolutely whacked lighting, since the normal map (the second dummy_texture used in the model::Material::new) is completely inappropriate here.

I have become Bull, destroyer of cows

We fire up the program, and what emerges is pure nightmare fuel: an unholy fusion of limbs and bovine flesh, a monstrous cow deity born of code and chaos.

Turns out the bull model is massive compared to the original cub. Like, not even in the same ballpark. Thus began my journey into understanding 🌈 model scaling 🌈.

Wait, how does 3D rendering even work again?

3D rendering uses a bunch of cool linear algebra to make 3D images appear on a 2D screen.

What most people don’t realise is that it’s all smoke and mirrors: you’re looking at a flat 2D projection of a 3D scene. With matrix math, we take 3D coordinates and transform them onto your screen. Do this meany times a second and suddenly - smooth animation that tricks your brain into thinking it’s real.

When we load a model, its coordinates are in what’s called object space. To render it in our scene, we transform it into world space. Along the way we can rotate, translate and scale it.

So how do we shrink our massive bull?

Enter: the bounding box.

A bounding box is just the smallest box that fits entirely around an object. We can use it to figure out how big the bull is, then scale it down to match our cube model in size.

Bounding boxes are useful for more than just scaling though - they’re used in basic collision detection - though I haven’t really touched that yet. Right now, I just want to not enact a demonic ritual each time I load my program.

Here’s the code I used to calculate a bounding box from an array of vertex positions:

fn calculate_bounding_box(vertex_positions: Vec<[f32; 3]>) -> ([f32; 3], [f32; 3]) {

let mut min = [f32::INFINITY; 3];

let mut max = [f32::NEG_INFINITY; 3];

for position in vertex_positions {

for i in 0..3 {

min[i] = min[i].min(position[i]);

max[i] = max[i].max(position[i]);

}

}

(min, max)

}

This function gives us the min and max corners of the bounding box - effectively the bottom-left and top-right points in object space.

Great! So now what?

Making scale happen

To scale the bull down, I measured each bounding box’s size and found their largest side. Then, I created a scaling factor: cube size divided by bull size.

impl BoundingBox {

pub fn new(bounding_box: ([f32; 3], [f32; 3])) -> Self {

Self {

min: bounding_box.0,

max: bounding_box.1,

}

}

pub fn size(&self) -> [f32; 3] {

[

self.max[0] - self.min[0],

self.max[1] - self.min[1],

self.max[2] - self.min[2],

]

}

pub fn max_extent(&self) -> f32 {

self.size()[0].max(self.size()[1]).max(self.size()[2])

}

}

let scaling_factor = cube_box.max_extent() / bull_box.max_extent()

And voila, we have a bona fide scaling factor to rein in those bulls.

Taming the Beast

Now we have a scaling factor that can be applied to our model matrix passed to our GPU shader.

For now I’ve jammed the scale into my instance struct, but I’ll probably refactor this to be more “model aware” later.

pub struct Instance {

pub position: cgmath::Vector3<f32>,

pub rotation: cgmath::Quaternion<f32>,

pub scale_factor: f32, // new scale factor - yay!

}

impl Instance {

pub fn to_raw(&self) -> InstanceRaw {

let scale = cgmath::Matrix4::from_scale(self.scale_factor);

let rotation = cgmath::Matrix4::from(self.rotation);

let translation = cgmath::Matrix4::from_translation(self.position);

let model = translation * rotation * scale;

let normal = cgmath::Matrix3::from(self.rotation).into();

InstanceRaw {

model: model.into(),

normal,

}

}

}

With scale in place, everything renders correctly.

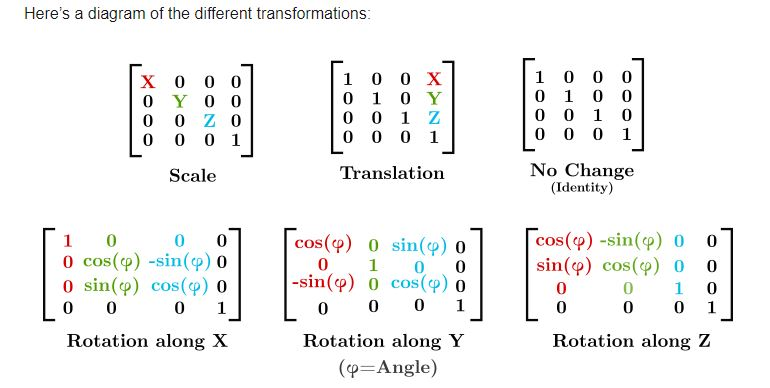

Without diving too deep into the math weeds, Fig 1 shows what this transformation looks like. Don’t stress if you don’t follow it, I’ll probably do a whole post on transformation matrices soon.

Applying this fix in the shader (sorry this post turned into a bit of a “draw the rest of the f***ing owl” situation), we finally get something beautiful. A lovely pasture of grazing bulls.

Wrapping up

That’s it for now. I’ve got some serious cleanup ahead since this was a quick hack job. But hey, I learned how bounding boxes work and I made my bulls less terrifying.

Stay tuned for more posts where I probably break stuff, glue it back together and learn something in the process.

Subscribe for updates

Want more like this? Get new posts in your inbox. No spam, ever.